The Silent Experts: Why Technical People Shy Away from Public Speaking

Table of Contents

In the tech industry, there’s often a disconnect between those who do the work and those who talk about the work. We’ve all been there: sitting in a conference hall, listening to a keynote speaker articulate a concept with supreme confidence, while thinking, “Wait, that’s not quite right,” or “I solved that problem three years ago in a much better way.”

It is easy to sit in the audience and critique. It is much harder to be the one holding the clicker.

There is a pervasive phenomenon where the most knowledgeable technical people—the ones architecting the systems, debugging the kernel panics, and securing the infrastructure—are the least likely to be found on stage. Conversely, the “thought leaders” we see on the circuit are sometimes surprisingly detached from the day-to-day reality of the technologies they champion.

I wanted to explore why this happens, and share why—despite the discomfort—I’ve decided to stop staying silent.

The View from the Stage #

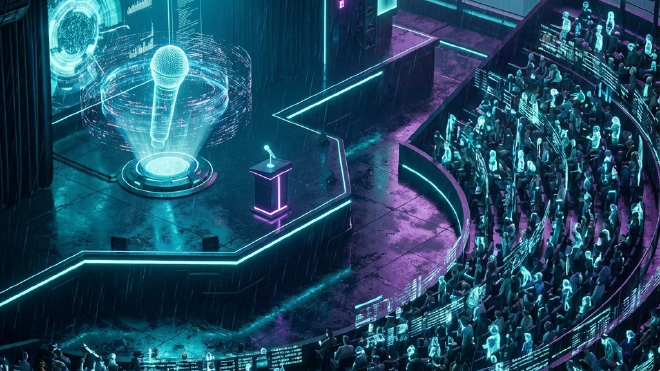

If you look at the picture above, you see a standard conference presentation. But what you don’t see is what’s happening internally.

In that photo, I am about as uncomfortable as I can possibly be.

For me, public speaking is the most challenging thing I do. It does not come naturally. I am a technical person by nature; I prefer the terminal to the podium. However, I’ve realized that this discomfort is exactly why I have to do it. It offers distinct rewards that “just coding” doesn’t provide:

- The Satisfaction of the Struggle: Doing something that scares you provides a unique kind of satisfaction. Overcoming that biological urge to run away and instead delivering value to an audience is a massive personal win.

- The Ultimate Forcing Function for Research: This is the secret weapon of public speaking. Because I am technical, and because I suffer from the fear of looking “unprofessional” or technically inaccurate, preparing for a talk forces me to do my best research. I cannot wing it. I have to know the subject inside and out, better than I would if I were just implementing it, because I need to be ready for the hardest questions.

- The Opportunity to Geek Out: This is arguably the best part. Being on stage acts as a massive icebreaker. It opens the door to incredible discussions with people in the hallway afterwards. It allows me to bypass the small talk and immediately “geek out” with other experts on the topics we are both passionate about.

The “Real Work” Fallacy #

For many of us, there is a deep-seated belief that public speaking, blogging, or “brand building” is not real work. Real work is shipping code, closing tickets, and solving hard architectural problems. Anything else feels like a distraction—or worse, vanity.

I used to believe this. I viewed communication as secondary to implementation. But I’ve learned that if you don’t tell your story, you cede the narrative to others who may understand the “what” but not the “how” or the “why.”

The Curse of Knowledge #

Ironically, the more you know, the more you realize what you don’t know. A junior developer might learn a new framework and immediately feel compelled to write a “Definitive Guide.” A senior engineer, having seen that framework fail in edge cases across distributed systems, might hesitate to speak because they haven’t mastered every single nuance.

This is the Dunning-Kruger effect in reverse. True experts are often painfully aware of their limitations. We fear being “found out” by the audience. We forget that our “basic knowledge” is often a revelation to 90% of the room.

Reclaiming the Stage #

The industry loses out on deep, battle-tested wisdom when technical experts stay silent. When the stage is dominated by professional speakers rather than practitioners, we get hype cycles instead of engineering truths.

If you are a technical person who hates the spotlight, consider this: Sharing your knowledge is a technical contribution.

When you solve a hard problem, that’s a unit of value. When you teach a thousand people how to solve that problem, that’s leverage. You don’t need to be a charismatic extrovert to be a great speaker. You just need to be honest, specific, and willing to share what you’ve learned in the trenches.

The community doesn’t need more polish; it needs more truth. It needs you.

Since I’ve argued that preparation is the most critical part of this process, I want to share exactly how I tackle it. In an upcoming post, I will describe my personal methodology for building presentations—from the deep-dive research phase to structuring the deck and the final delivery.